Change of all varieties (especially organisational transformation) rarely gets completed and sustained in the way we might hope and plan for. Experiencing that divergence between the plan and reality, or even failing to deliver the impacts you wanted, can feel terrible and disabling, leading to dents in confidence, increased risk aversion and ultimately shying away from pursuing change.

In some walks of life that might not be too serious, but if you are an HR change professional then it could be career limiting. So, when the wheels start to come off, how can you become anti-fragile, to use a term made popular by Nassim Taleb?

Change has always been difficult

The great news is, there is an approach that will help you and its practice is almost as old as history itself. Indeed, the Stoic philosophers had a term for it, Premeditatio malorum. Fiction heroes have a catchphrase for it, “Hope for the best, plan for the worst.” I was lucky enough to be introduced to it in the mid-1980s when my sports psychologist had me visualise what she called, “Worst case scenarios.” If it has worked for so many people, from so many different domains, over such a long period, you could well benefit from it too.

Why plan for a failed organisational transformation?

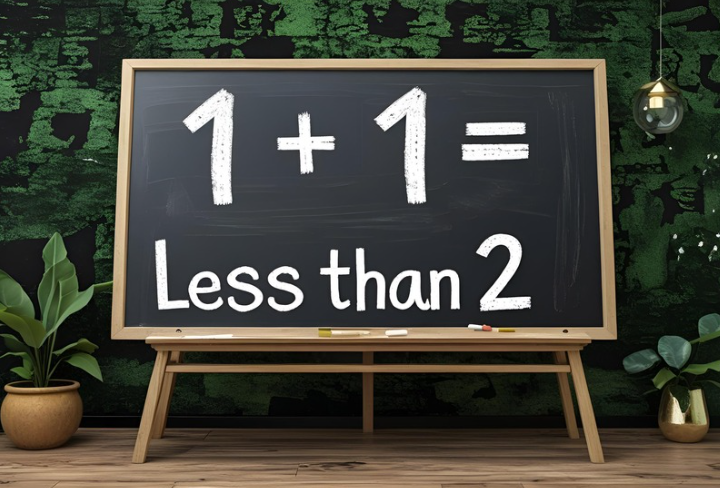

Latest research from Mckinsey Group, suggests that even successful organisation transformations, do not deliver all their objectives and value. So, armed with that evidence, plus your own experience, you can pretty much guarantee that any change effort will not pan out exactly as you want to. You may get most of the impacts, some of the change or only a small part but you are unlikely to get all of what you hoped and planned for. Or perhaps you get it all but not in the timeframe you had scheduled.

If you go into change efforts of any sort – diet, learning, fitness push or cultural change – with the knowledge that whilst you have done as much as you can to deliver what was agreed, you know, somewhere along the line, things will not happen as you want, that insight can be really liberating. It takes away the destabilising effects of any deviations. As I was once told, “The problems never go away, they just change shape.” You are prepared for a knock and you can right yourself more quickly.

More than that, you can actually set out another layer of planning, namely:

- How you plan to respond emotionally to the bump in the road and how you can help others too.

- How you will adapt the plan, in order to get back on track.

- How your planning will change for the next project, to reflect what you have learned.

So, whilst no-one would actively wish for organisation change efforts to go wrong, the advantages of being aware of the likelihood of it happening and preparing for that event gives greater certainty, allows for planning how you will respond both at a personal level but, importantly, also in your role as the leader of the change effort.

Exigence works with organisations to deliver full-stack HR leadership development solutions, from Executive and senior team coaching to Concise Coaching and Team Coaching. If you would like to discuss how we can help you deliver quantifiable impacts for your organisation, we’d love to hear from you – just contact us here.